What's Your Type; An AI Resurrection

January 2026

Introduction

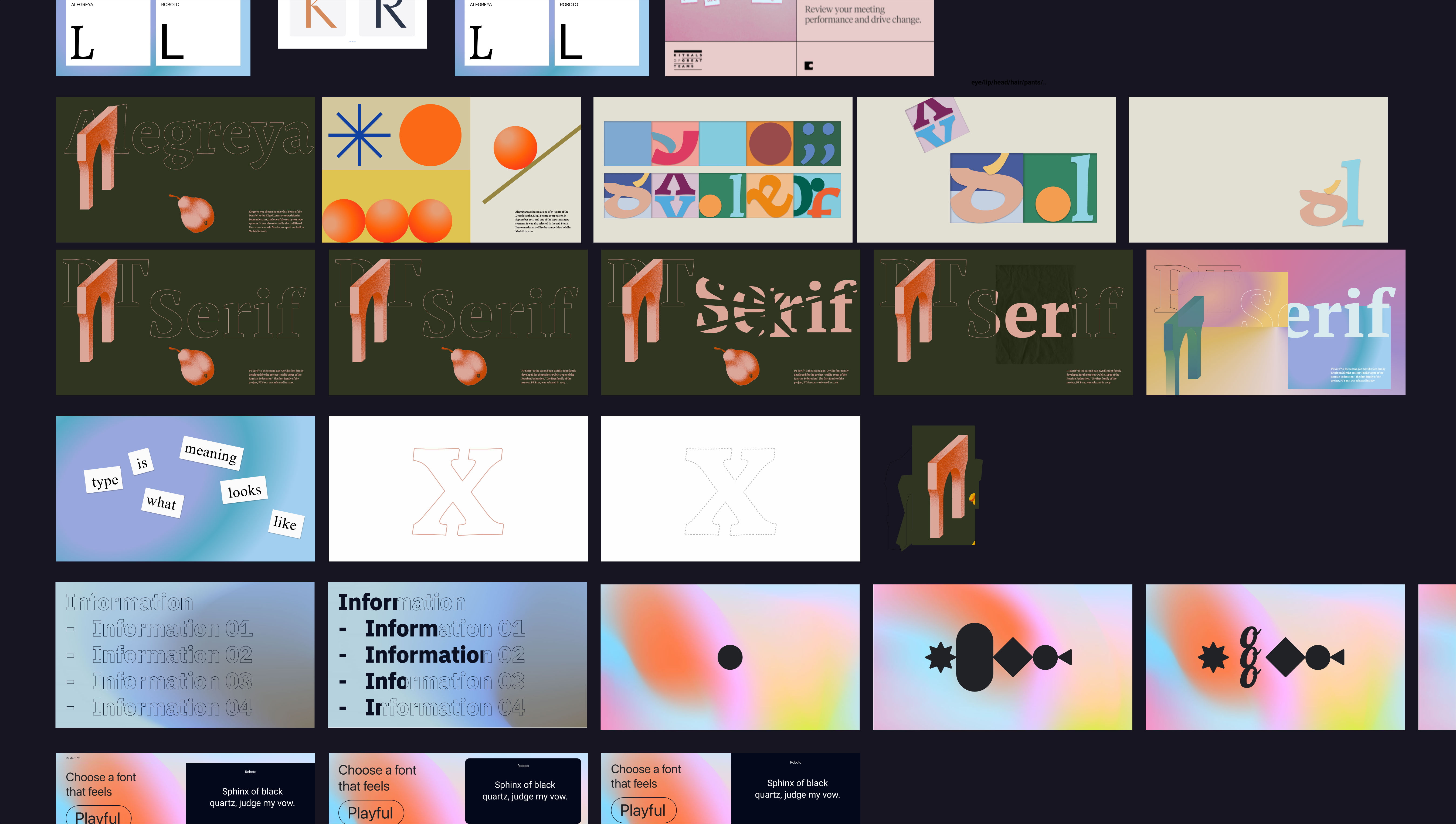

Open-source fonts are ubiquitous on the Web, and yet we understand very little about the implicit connotations and underlying perceptions that users have of them. Nor do we understand how these perceptions vary across cultures and languages. What’s Your Type seeks to understand these font connotations and perceptions through a web-based survey.

I was a part of the team that designed this survey in 2022, while a member of the Computational Creativity Lab at Carnegie Mellon University, the survey asks users to pick the font that best matches an emotive adjective—such as “playful,” “informative,” and “trendy.” By gathering user responses, What’s Your Type crowdsources a database of font preferences, searchable by language and nationality of the respondent. Our hope was to launch this survey and use the data to examine how associations differ across geography, language, and eventually other demographic characteristics.

We completed the design in the spring of 2022, but ran into an all too common problem–we didn’t have the resources or expertise to complete development. The semester ended, some of the team graduated, and the Figma file sat unused. An unrealized project.

Four years later and the world of software development and design has changed. AI coding agents have changed what’s possible for a nontechnical builder like myself. And in an effort to explore what’s possible, I set out to build What’s Your Type over the New Year holiday. It worked wonderfully and I’m pleased to share the survey here. Please take the survey and reach out with feedback.

Resurrecting this project was my first exploration into a full-stack AI build, with a feature-complete experience that recreated the UI polish of the designs. Here are some brief takeaways from the experience:

Differentiated design hasn't been automated

Cursor could have built functionally the same survey tool for me without any designs, but it would have looked like a generic Google Form. And sure, you could have plugged in a few style keywords and gotten some pastiche visuals. But for this experience, the visual design is as much a part of the experience as the survey logic itself. And to truly invest in a visual experience, there’s a level of time and control that I haven’t found to be possible with AI. To invest in that visual design meant pulling inspiration references, discussing overall mood, and working through multiple format iterations. We knew what needed to exist functionally, but the conversation was how to create something engaging and experimental, which highlighted the typefaces. There are other AI tools that could have accelerated this visual exploration process, but a part of it had to involve human judgement and taste. One-shoting the concept in Cursor could have produced the same results functionally, but not experientially.

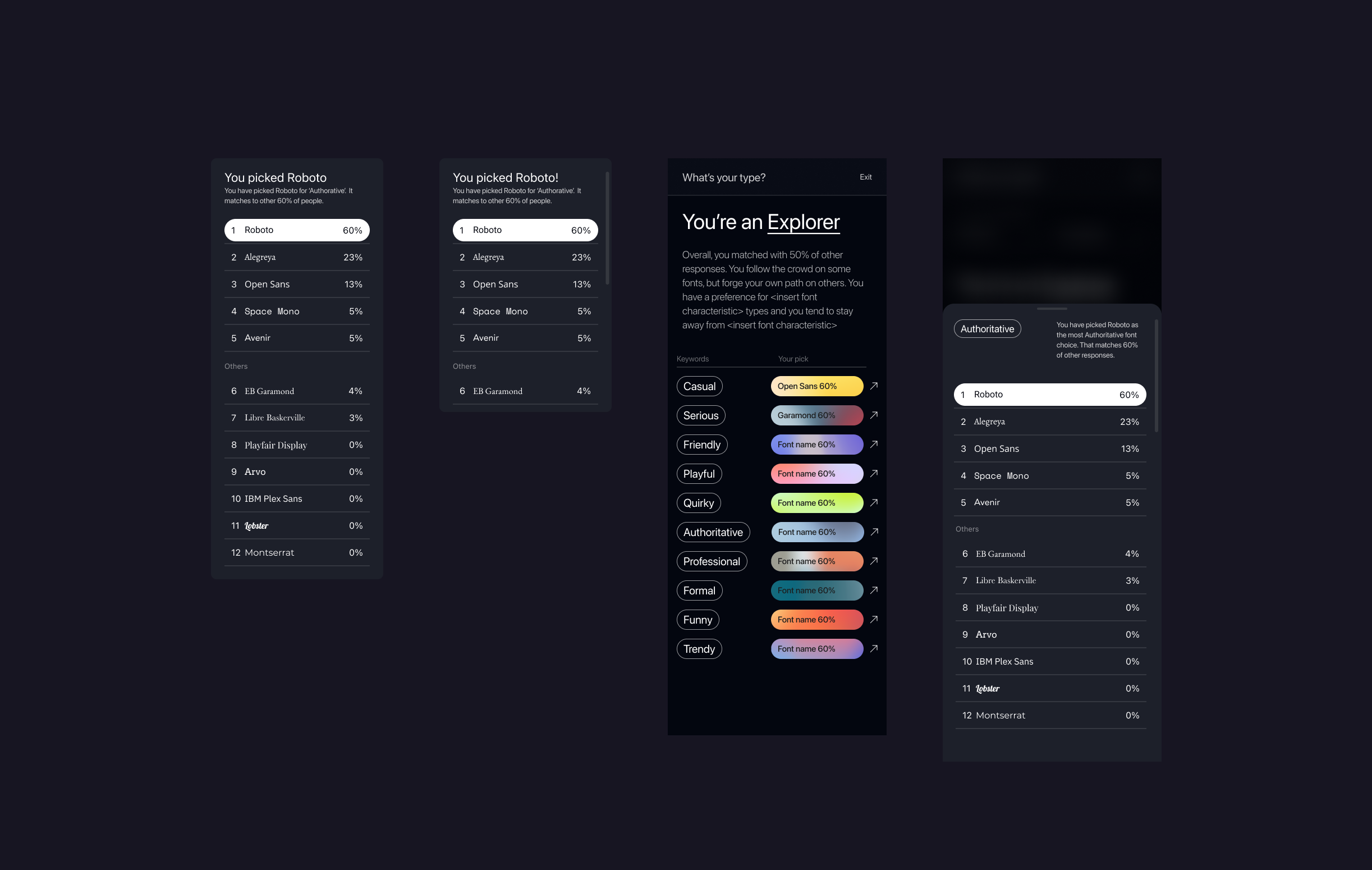

Prompting inefficiencies for design

Halfway through my build with Cursor, the survey was nearly pixel-perfect—except for the results tooltip. It was incomplete and lacked visual polish. I initially tried to prompt my way to a fix, but the manual back-and-forth was tedious and time consuming. I pivoted back to Figma, rebuilt the tooltip with proper Auto Layout and scroll behaviors, and then used the Figma MCP. This time, Cursor nailed the implementation in one shot. I got the best results when I followed this path, design in Figma and prompt Cursor to implement. The back-and-forth of prompting become an inefficient mechanism for these edits.

AI for the last 30%

Much of the AI-design content today discuss AI prototyping tools as a way to accelerate exploration and ideation, let’s call it the the first 30% of the design process. Tools like Magic Patterns, V0, Bolt, Figma Make etc. are promoted as a way to quickly create an interactive first draft. While I’m sure there’s value to that, what struck me during the this project was how building a full fidelity version of the complete design in Cursor prompted me to think through the realities of an interactive web experience much more rapidly than in Figma. I was conducting the kind of tweaking that usually comes out in a quality assurance process with a developer: (ie “The layout get’s awkward at around 2000px. Let’s add a max-width to the primary content, but have the background extend to 100% of the viewport width”).

That’s kind of fine-tuned adjustments is usually the first thing to get cut in a prioritization conversation, and those lost details add up into a ultimately unsatisfying and unconsidered experience. It was empowering to have control over those details. To know that users would get the experience as I intended, and not have to rely on someone else to understand my intentions and care enough about design minutiae to implement it.

The traditional design developer workflow doesn't make sense

If there’s one AI take this experience has completely convinced me of, it’s that product designers need to be active contributors to front-end development. If you’re designing a software product, the goal should be to push code on the product. Designers are shepherds of the user experience and there’s no better way to ensure the fidelity of that experience than by crafting it in the medium where users experience it. The process of working with tools like Cursor reveals how much is lost when you only design using a static design software.

To work and think in code also seems like a natural evolution in the trajectory of design software over the past decade. Figma has increasingly pushed features that bring the structure and syntax of development into a design GUI–design tokens, auto-layout, variables. Meanwhile, AI tools like Cursor and Claude code with Figma MCP have made it possible to translate design files into code at a high fidelity. We’re reaching a point of convergence between design software and coding tools. In the future, I could see a tool that’s a cross between Figma, Webflow, and Cursor. Where you can build and edit an interface via prompting and make direct it’s in the GUI that are reflected in the codebase.

Using Cursor for a personal project is one thing; bringing it into my client work for large enterprise clients is another. I’m energized about the possibilities, but also realistic about the hurdles–complexities around scale, security, and collaboration. In a future post, I look forward to exploring how these tools fit into a messy real-world, client-facing design process.